The Archive in 100 Objects

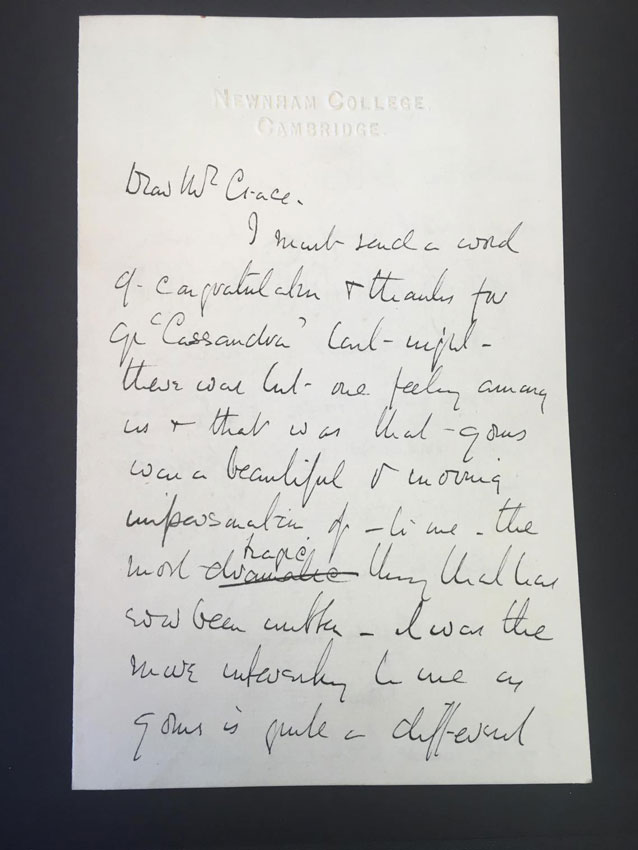

In this series, researchers explore the larger stories told by single objects in the archive. Here, Dr Marchella Ward (acting Archivist-Researcher) takes on the first object, a letter from the classicist Jane Ellen Harrison to young Cambridge student J.F. Crace, donated to the APGRD by Crace's daughter, Anne Watson.

In this series, researchers explore the larger stories told by single objects in the archive. Here, Dr Marchella Ward (acting Archivist-Researcher) takes on the first object, a letter from the classicist Jane Ellen Harrison to young Cambridge student J.F. Crace, donated to the APGRD by Crace's daughter, Anne Watson.

“I have never before seen a man play a woman’s part without intruding the ‘false-feminine’ – and thoroughly ruining the ‘fervour and pity’ of it”.

“I have never before seen a man play a woman’s part without intruding the ‘false-feminine’ – and thoroughly ruining the ‘fervour and pity’ of it”.

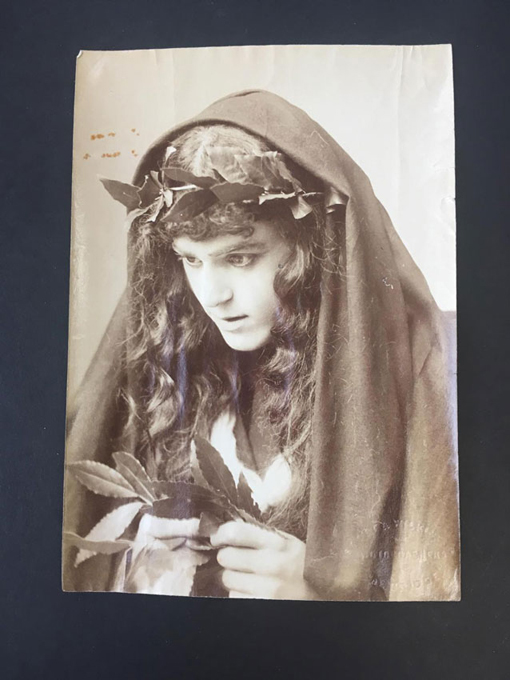

So wrote the classicist Jane Harrison to the student actor she names only as 'Mr Crace’. Far from the most well-known of her acquaintances (Harrison counted a stable of prime ministers as well as George - and much later T.S. - Eliot among her friends, and had published frequently in a periodical edited by Oscar Wilde), Crace, who would later become a Classics tutor at Eton, had just appeared in the role of Cassandra in an ambitious student production of Aeschylus’ Agamemnon at the University of Cambridge in 1900.

Harrison’s attendance at the play is by no means surprising: she spent most of her professional life as a classicist at Newnham College, Cambridge, having learnt both Latin and Greek (as well as German, French and Hebrew) from a series of governesses in her native Yorkshire. Nor is her positive review of the play particularly extraordinary. Many of the reviews highlighted Crace’s talents, with the Guardian of 28 November 1900 commenting: “Mr Crace’s impersonation of Cassandra was nothing less than superb”. These reviews, though, may have come as some surprise to those who were part of the rehearsal process, which was plagued by quarrelling directors, an over-zealous conductor and a Watchman with a bad case of stage-fright: “…it was a serious matter of doubt”, quipped the novelist E.F. Benson, “whether his shaking knees would ever take him safely down his somewhat rickety watchtower”.

And rehearsals nearly never began at all, thanks to their constant interruption by Clytemnestra’s dog: “The rehearsal will proceed when the leader of the Argive elders has quite finished playing with a bull-dog. Please send the bull-dog out of the theatre”. Eventually, though, the company pulled themselves together. After all, performing the Agamemnon was a seriously competitive field: Oxford University’s performance of the play just over twenty years earlier had been so successful, one Times journalist reported rather too proudly, that the play even transferred to London.

More surprising than the sudden turn around in the play’s fortunes, however, is the fact that Harrison appears, in her letter, to support a male actor playing a female role. Although she qualifies her praise (she has “never before” seen a man so capable), Harrison’s comment is testimony to a strange discontinuity of logic of which she, both a prominent suffragist (if not quite a suffragette) and the first female professional academic, would have been acutely aware.

Right: Crace in the role of Cassandra, Cambridge Agamemnon, 1900. APGRD Collections.

Photograph © APGRD

Women had been able to tread the boards of the professional English stage at least since Margaret Hughes took on the role of Desdemona in 1662 (and indeed, by Jane Harrison’s time women had played even the title role in Shakespeare’s Othello), and the role of Cassandra had been played in the 1880s to much acclaim in Edinburgh and London by both Mrs Fleeming Jenkin and Miss Dorothy Dene respectively. In Cambridge, just as in Oxford (where the role of Cassandra in 1880 had been taken by Mr George Lawrence), however, a woman in the role of Cassandra remained impossible.

Despite the industry and ingenuity of pioneering women scholars like Jane Harrison, it was not until 1948 that women would become full members of the University of Cambridge, and were finally eligible to receive its degrees. The total absence of women from the stage in the Cambridge Agamemnon was a ghostly echo of its performance in ancient Athens in 458 BCE, where there would have been no women either on the stage or – as some scholars still argue – in the audience.

There is something strangely perverse about the idea of Harrison celebrating Crace’s performance in the role of Cassandra, when this was necessitated by the very same University statutes that kept her cloistered in Newnham College and denied her recognition in the form of a formal University degree. For an academic who once drew an audience of sixteen hundred people for her lecture on Athenian tombstones in Glasgow, the shortsightedness in the University’s sidelining of its female staff and students must have been obvious.Towards the end of her letter, Harrison offers Crace some slightly barbed advice on how best to manipulate the drapery that comprised his costume (“only one drapery suggestion!”). By closing her letter not on the effectiveness of his performance, or the musical quality of his Greek, but on his inability to know – as a woman might have done – how best to manage his flowing dress, Harrison quietly undermines the dominant view that men could be just as good at playing female roles as women.

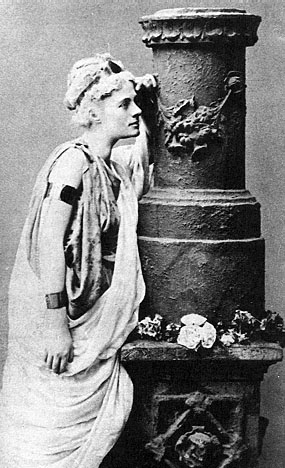

That Harrison should know how to deal with elaborately draped costumes better than most is fitting. In 1887, the Vice Chancellor of Oxford University had made an exception to the usual rules that kept women off the stage, and allowed her to play the title role in a student production of Euripides' Alcestis. Her skilful manipulation of the heavily draped costume and sympathetic gestural performance were heavily praised by the press, but for the reviewer of the literary magazine The Athenaeum, there was one problem with her performance: “she pitched her voice throughout in too high a key”. In other words, audiences in Oxford were not accustomed to hearing women’s voices speak women’s roles.

Right: Harrison as Alcestis in the 1887 Oxford student production. Photograph: Newnham College, Cambridge.

Right: Harrison as Alcestis in the 1887 Oxford student production. Photograph: Newnham College, Cambridge.

And, just as her character Alcestis did at the end of the students’ play, Harrison too would return to life after her death. She appears briefly as the ghost in Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, running across the lawn, her draped nightdress billowing out behind her. Just as Woolf’s accomplished ancient language skills lie behind her self-effacing essay On Not Knowing Greek, the image of a ghostly Jane Harrison running across Newnham College lawn showed not that women had only a limited place in the study of Classics at Cambridge, but that they were there in full view out on the lawn at the centre of academic life. Cassandra may, for male reviewers, have been convincingly embodied by the young Mr Crace, but for Harrison it was a role that would have been better played by one of her accomplished young female students, well aware of the difficulties of the drapes and trappings of Classics at Cambridge in the nineteenth century.

Find out more

- About Marchella Ward

- See more images from the production and further discussion of Harrison's letter and Crace's Cassandra in the APGRD's free multimedia/interactive iBook, Agamemnon, a performance history (iBook available on Apple Books)

- To read more on the difficulties of costuming ancient characters onstage and male actors' recurring struggles with the drapery required for female ancient roles, see Rosie Wyles' An introduction to... tragic costume.

- On the university context of Crace and his contemporaries' stagings of ancient plays in ancient languages, see Clare Foster's Short Guide to School and University Productions of Ancient Plays.