A guest post by Chris Vervain

Recently, Dr Chris Vervain, a performer and maker of masks based in London, sent material relating to her most recent production, Medea Without the Men (February 2018), to the APGRD. In this guest blog post, she tells us more about that production, and how it was informed by her interest in working with masks as a performer and director.

Recently, Dr Chris Vervain, a performer and maker of masks based in London, sent material relating to her most recent production, Medea Without the Men (February 2018), to the APGRD. In this guest blog post, she tells us more about that production, and how it was informed by her interest in working with masks as a performer and director.

Why should we perform Greek drama in masks today? My own reason for doing so is probably different from that of most directors. Initially I became interested through working as a performer of mask and physical theatre inspired by modern pioneers such as Jacques Copeau (wikipedia entry). In this kind of practice the mask is seen as an essentially non-verbal genre, with meaning conveyed by the language of the body: sound, gesture and movement. And yet, I knew that the masked dramas of ancient Greece and Rome had complex and poetic texts. It was the challenge of discovering how we today might perform the ancient plays in mask that first excited my interest.

Why should we perform Greek drama in masks today? My own reason for doing so is probably different from that of most directors. Initially I became interested through working as a performer of mask and physical theatre inspired by modern pioneers such as Jacques Copeau (wikipedia entry). In this kind of practice the mask is seen as an essentially non-verbal genre, with meaning conveyed by the language of the body: sound, gesture and movement. And yet, I knew that the masked dramas of ancient Greece and Rome had complex and poetic texts. It was the challenge of discovering how we today might perform the ancient plays in mask that first excited my interest.

Masked performances of Greek tragedy raise a number of different questions. Are the plays essentially rooted in 'ritual dance’ with the chorus playing a central role? Or are they better understood as the enactment of heroic myth, with the chorus acting as a sort of collective character? Does mask inevitably lead to a 'ritualistic' interpretation? Were the ancient masks individually characterised or, were they neutral in expression; idealised types, distinguished only by gender, age and perhaps status? Does the mask require a different approach to the usual, broadly Stanislavskian style of acting? What should a director make of Peter Hall's statement that: "masks cannot be directed"? (in a platform discussion, 21 September 1996, at the Olivier Theatre.) I have discussed these and other related questions in my PhD thesis, and in a number of articles (see my website for references and links to online sources).

Above: Masked performers play the Furies in Vervain Theatre's 'Eumenides', 2016. Image reproduced by kind permission of Chris Vervain.

Above: Masked performers play the Furies in Vervain Theatre's 'Eumenides', 2016. Image reproduced by kind permission of Chris Vervain.

My work, then, is research based and seeks to re-invent a lost tradition of masked performance. We don't really know how the ancients approached their roles, and there is no reason to suppose that ancient theatrical conditions operated in the same way as ours. As modern theatre practitioners we have to work with our own understanding of what makes for ‘good’ theatre.

The performers who I work with bring their various areas of expertise, be that in acting, dance, or music, and I introduce them to the mask (and my particular masks) and demonstrate some of the techniques I have learned from modern mask and physical theatre practice. They love the plays; and they also love the masks and often find their own names for them: one mask for one of my old men, who has appeared in several of our productions including our most recent one, goes by the name ‘Boris’ among members of the company! Very soon we have a common language of masked staging for the ancient plays, one that we feel will make sense to a modern audience. Using our actor's training we also try to follow a character's thought processes, and to find a reason for what they say and why they act the way they do.

Right: Drawing by Chris Vervain depicting two performers preparing for masked roles in a female chorus, after the Boston Pelike (Museum of Fine Arts Boston). Image reproduced by kind permission of Chris Vervain

Right: Drawing by Chris Vervain depicting two performers preparing for masked roles in a female chorus, after the Boston Pelike (Museum of Fine Arts Boston). Image reproduced by kind permission of Chris Vervain

I use a very simple 'set', consisting of a performance space that in some respects emulates that of the ancient theatre, in that it is large enough to accommodate choral dance, has an upstage wall (corresponding to the ancient skene) and entrance/exits from the sides and from upstage. I also try to find some means of elevating protagonists above the chorus for some scenes. This is usually achieved by providing them with a box to stand on. Although my mask designs broadly follow what we know about ancient masks, and costumes are in keeping with these Greek-style masks, I make no attempt to replicate those of the ancient performances. I do not see myself as conducting theatre archeology, but rather removing the practice of Greek tragedy from the specifics of its original culture and finding a more archetypal dimension.

Medea Without the Men (February 2018) was a performance by my company of selected scenes from Euripides’ play in English translation at Creation Box at Makespace Studios in London. It was a piece created over a ten-day workshop process, focusing on choral dances. All of the chorus members were dancers by profession (although two of them also had actor training), and in this performance they danced whilst offstage actors spoke the text. Their superior spatial awareness meant that after a few days of working together in mask, there were no collisions despite the fact that a complex choreography was being demanded of them.

Left: choral dancers perform in Vervain Theatre’s 'Medea Without the Men', 2018. Image reproduced by kind permission of Chris Vervain.

Left: choral dancers perform in Vervain Theatre’s 'Medea Without the Men', 2018. Image reproduced by kind permission of Chris Vervain.

One of the advantages of using masks in the performance is that a small adult can take the role of a child, with some degree of credibility. This allowed us to have one of Medea’s sons – played by me –onstage for a number of the scenes. The child was present for the exchange between the nurse and the tutor, playing with a toy horse; and throughout, as a performer I had to remain aware of the specific technical demands made by the mask. I needed to glance up momentarily once or twice to show my mask to the audience, and to send the horse well downstage just before the tutor came towards me, so that the prop did not become a tripping hazard - especially important for the limited vision of the actor in mask. This kind of double awareness, both of the role and of the technical demands of the mask is crucial to masked performance.

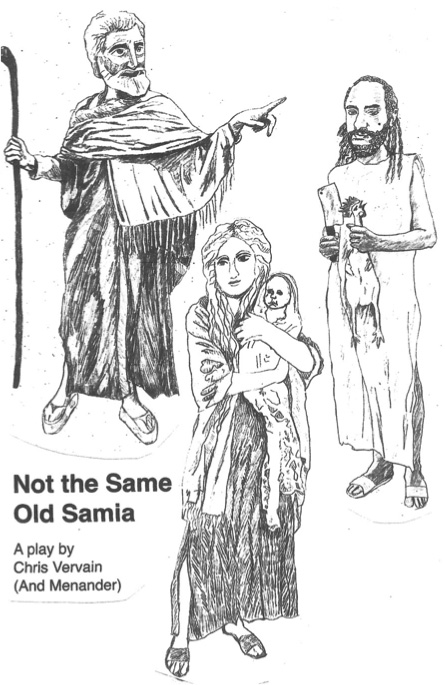

For my next project I will be moving away from tragedy and into New Comedy. I have produced my own performable version of Menander’s Samia, in which I re-tell the story from the point of view of Chrysis, so that it becomes, in my version, Not the Same Old Samia. I have retained the extant text but also added new material: including a full set of choral odes. The script has received an initial rehearsed reading, and we will be running a preliminary workshop to try out some of the New Comedy masks with the actors in the near future. The masks for this production are largely stock character types inspired by some of the ancient images and artefacts depicting those of New Comedy. The plays seem to call for a presentational style of acting, with direct address to the audience an important element.

For my next project I will be moving away from tragedy and into New Comedy. I have produced my own performable version of Menander’s Samia, in which I re-tell the story from the point of view of Chrysis, so that it becomes, in my version, Not the Same Old Samia. I have retained the extant text but also added new material: including a full set of choral odes. The script has received an initial rehearsed reading, and we will be running a preliminary workshop to try out some of the New Comedy masks with the actors in the near future. The masks for this production are largely stock character types inspired by some of the ancient images and artefacts depicting those of New Comedy. The plays seem to call for a presentational style of acting, with direct address to the audience an important element.

Right: Cover image for Not the Same Old Samia. Image reproduced by kind permission of Chris Vervain.

Find out more

- About Chris Vervain

- Watch Vervain Theatre’s 2016 performance of Two Plays by Aeschylus at Theatro Technis in Camden: Aeschylus' Choephori (YouTube) and Aeschylus' Eumenides (YouTube)

- To read more about the ways an actor uses his/her body while performing in a mask, see Stephe Harrop's An introduction to... the tragic body

- Chris Vervain, 'Performing Ancient Drama in Mask: the Case of Greek New Comedy', New Theatre Quarterly, 79 (August 2004), pp245-64

- Chris Vervain and David Wiles, 'The Masks of Greek Tragedy as Point of Departure for Modern Performance', New Theatre Quarterly, 67 (August 2001), pp254-72

- Chris Vervain, 'Three Electras and the Multivalent Mask', Didaskalia Vol.7 (2007)

- Chris Vervain, 'The Masked Chorus in Action: Staging Euripides Bacchae', Didaskalia Vol.8 (2011).

- Chris Vervain, 'Performing Ancient Drama in Mask: the Case of Greek Tragedy', New Theatre Quarterly, Vol.28:2, (May 2012), pp163-81

- Christine M Lambert, Performing Greek Tragedy in Mask: re-inventing a lost tradition, PhD Thesis, University of London (2008).