A guest post by Natalie Pla

The APGRD recently received a visit from Natalie Pla (University of Bristol) who has been writing her masters thesis on two Nigerian adaptations of Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannus. As well as bringing with her some exciting new material for the APGRD’s collections, she also filled us in on some of the insights that she has made in the course of her work. In this post, Natalie introduces us to her research.

The APGRD recently received a visit from Natalie Pla (University of Bristol) who has been writing her masters thesis on two Nigerian adaptations of Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannus. As well as bringing with her some exciting new material for the APGRD’s collections, she also filled us in on some of the insights that she has made in the course of her work. In this post, Natalie introduces us to her research.

My research explores the reception of Greek tragedy in Africa today. It traces a line of interpretations from Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannus c. 429BCE, to the 2013 Nollywood adaptation film, The Gods Are Still Not to Blame. My journey into this body of work began at undergraduate level, where I first encountered the Nigerian playwright Wole Soyinka’s adaptation of Euripides’ Bacchae (1973), in a class on the legacy of classical literature. I found Soyinka’s take on the ancient Greek play captivating, as it used the narrative from Euripides’ play to evoke important historical events such as Nigeria’s civil war and the transatlantic slave trade. It also introduced me to a whole new pantheon of Yoruba gods such as Ogun (god of metals with a penchant for palm wine), whose legend and iconography is associated with the Greek god Dionysus (Greek god of theatre and wine) in the play.

Right: A Yoruba statue representing a celebrant of the god Ogun, from the Museu de Arte de São Paulo. Image from Wikimedia Commons CC-BY-3.0.

After reading Soyinka’s captivating take on Euripides’ Bacchae, I was intrigued to see whether there had been any other adaptations of Greek tragedy by African writers. Sure enough, there were, and the most influential proved to be The Gods Are Not to Blame (1968), an adaptation of Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannus by Ola Rotimi.  The Gods transports the traditional Sophoclean narrative to the imagined precolonial Yoruba kingdom of Kutuje.

The Gods transports the traditional Sophoclean narrative to the imagined precolonial Yoruba kingdom of Kutuje.

Characters are updated to suit this new context: Odewale, Ojuola, and Baba Fakunle replace the familiar Oedipus, Jocasta, and Tiresias. Whilst the premise of the story remains largely the same, the dialogue is infused with Yoruba proverbs and scenes are added which make reference to traditional Yoruba folklore.

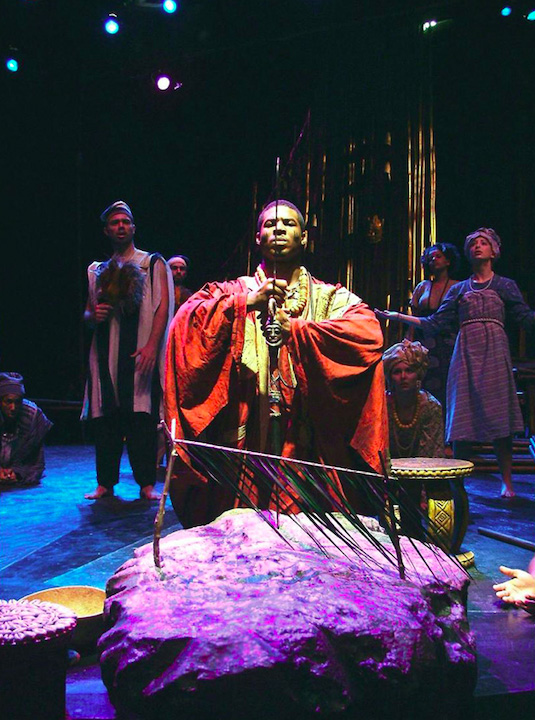

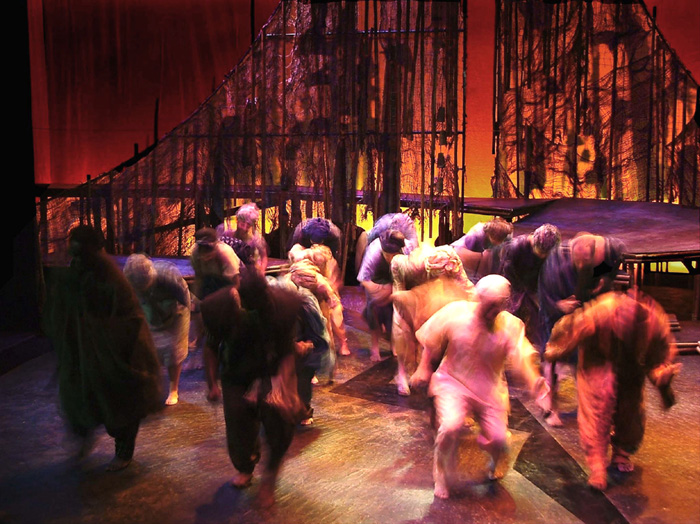

Elements of this Yoruba context were beautifully brought out in a production of The Gods Are Not To Blame, directed by Esiaba Irobi at Ohio University's Forum Theatre in 2004. (Photos, right and below, by kind permission of the designer, Natalie Taylor Hart).

The interviews, articles and reviews that I donated to the APGRD as sources of evidence for the 1968 premiere show the extent of Rotimi’s success in producing what has now become a canonical text in its own right. 74 years after its first performance, The Gods has been performed in Nigeria, Ghana, England, and Ireland. As these sources demonstrate, the play has proven particularly popular with directors who are part of the Nigerian diaspora in the UK. In the London-based Nigerian writer Belinda Otas' interview with Femi Elufowoju Jr, director of the 2005 Arcola Theatre production, she claims:

“I have never looked back since I saw The God’s Are Not To Blame [at the Arcola theatre]. It reawakened my passion for theatre, the way I had known it at home before I came to the UK. It also assured me that I could write about Africans and someone would see the artistic value of my work…”

In the same interview, Femi Elufowoju Jr comments on his first encounter with Rotimi:

“My growing up was interesting… I was moved to live in Ife with my aunt. There, I was taken to Oyelokun theatre to see ‘The gods are not to blame’. There I decided I was going to become a thespian.”

In Ireland, Bisi Adigun (who directed the play in 2003 and 2004) used the The Gods for the debut production of his own Irish African diaspora theatre group ‘The Arambe Theatre Company’. The group’s primary aim was to explore the construction of Irish identity from a diasporic perspective, which included a cast largely made up of immigrants and people of African descent. As these sources illustrate, Ola Rotimi’s adaptation of Sophocles holds a substantial cultural significance even in the twenty-first century. My MPhil research ‘Oedipus in Nigeria: Classical Adaptation / National Classic’ focuses on two present day theatrical and cinematic reworkings of Rotimi’s play, both provocatively titled The Gods Are Still Not to Blame. While most adaptations ask to be considered independently from their makers, the titles of these contemporary productions imply that a comparison with their literary predecessors is in fact desired. Here, the temporal distance between the adaptations of Oedipus tells a story of how Nigeria has changed socially and politically in the years since gaining its independence.

Written by Otun Rasheed in 2011, the theatrical adaptation The Gods Are Still Not to Blame brings Rotimi’s drama to the twenty-first century. Stephen (Rasheed’s version of Oedipus) has been raised in the USA and sent to fight in Afghanistan before he decides to travel to Nigeria in search of his origin story. In an interview I conducted while writing my thesis, Rasheed told me that this play built on some of the criticism that Rotimi’s play received for not depicting the African experience in an honest light. For this reason, the playwright makes some notable alterations to the 1968 version, such as the removal of the blinding of King Oedipus that is the focus of the final moments in Sophocles. This act of violence, he points out, would not befit a Yoruba king:

“Blinding is not the punishment for a king in African tradition. In Africa, when a king commits such a taboo there is a calabash that the priests or traditional chiefs will keep inside the palace for the king. The king is instructed to go inside and open up the calabash, which will contain poison or something that when he uses he will die. This is the traditional model in Africa.”

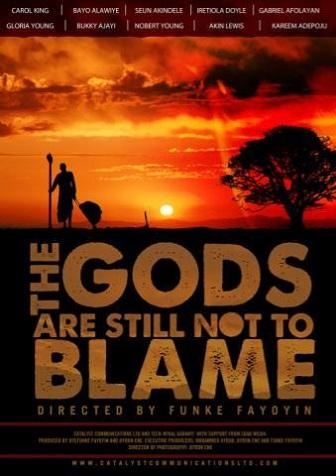

After its first performance at the University of Lagos theatre, the script quickly caught the eye of Oyefunke Fayoyin, a Nigerian film director. Fayoyin transformed Rasheed’s playtext into a feature-length Nollywood (a term created by fusing ‘Nigeria’ with ‘Hollywood’ to describe the third largest film industry in the world) film in 2013.  Nollywood films are often characterised by their interweaving plot structures and high level of dramatic content. Fayoyin’s interpretation of Rasheed is certainly no exception.

Nollywood films are often characterised by their interweaving plot structures and high level of dramatic content. Fayoyin’s interpretation of Rasheed is certainly no exception.

Right: Poster for the 2013 film The Gods Are Still Not To Blame, directed by Funke Fayoyin. Image links to source on nollywoodreinvented.com.

Although the film was released in 2013, it has not had an official UK premier until now. On the evening of 21 March 2018, Oyefunke Fayoyin herself will formally introduce The Gods Are Still Not to Blame to a UK audience for the first time at the University of Bristol. After the screening, there will be a panel discussion with representatives from Classics and Film Studies; tickets are free to download from Eventbrite.

The images from the 2004 performance of The Gods Are Not To Blame at Ohio University's Forum Theatre were reproduced here by kind permission of the production's designer, Natalie Taylor Hart. The director was Esiaba Irobi. Costumes were designed by Renae Pederson Skoog, and lighting designed by Dan Brunk.

Find out more

- You can read more about Wole Soyinka’s Bacchae and the larger context of these Nigerian adaptations in Justine McConnell's Short Guide to Postcolonialism and Classics.