The Archive in 100 Objects

In this series, researchers explore the larger stories told by single objects in the archive. Here, our acting Archivist-Researcher Dr Marchella Ward looks at what a production diary kept by the Flemish playwright Stefan Hertmans can tell us about Flemish-language adaptations of Greek tragedy.

In this series, researchers explore the larger stories told by single objects in the archive. Here, our acting Archivist-Researcher Dr Marchella Ward looks at what a production diary kept by the Flemish playwright Stefan Hertmans can tell us about Flemish-language adaptations of Greek tragedy.

“Everyone who writes about Antigone, appropriates her for him/herself”, wrote Hertmans in his production diary, published in the Flemish-language quarterly cultural magazine Nieuwzuid (2001). The diary, entitled ‘Antigone Aantekeningen’ (‘Annotations on Antigone’), was Hertmans’ attempt to justify his own own appropriation of Antigone in a production that had the English title Mind the Gap, and was produced by Toneel Groep Amsterdam and directed by Gerardjan Rijnders at the Kaaitheater in Brussels in 2001. Mind the Gap takes place in an underworld that looks startlingly like London’s Underground: “the world of Mind the Gap is an underground world, a modern Hades, the end of time where everything has already happened and where it is too late for anything at all”. However, unlike the ineffectual voice of the tannoy on the London Underground warning commuters to “mind the gap”, in Hertmans’ underworld, the voices of three women from Greek tragedy cannot be ignored. Between suited commuter versions of Eteocles and Polyneices, and a stumbling old man named Oedipus, the gaps in Mind the Gap are filled by the echoed voices of Antigone, Clytemnestra and Medea.

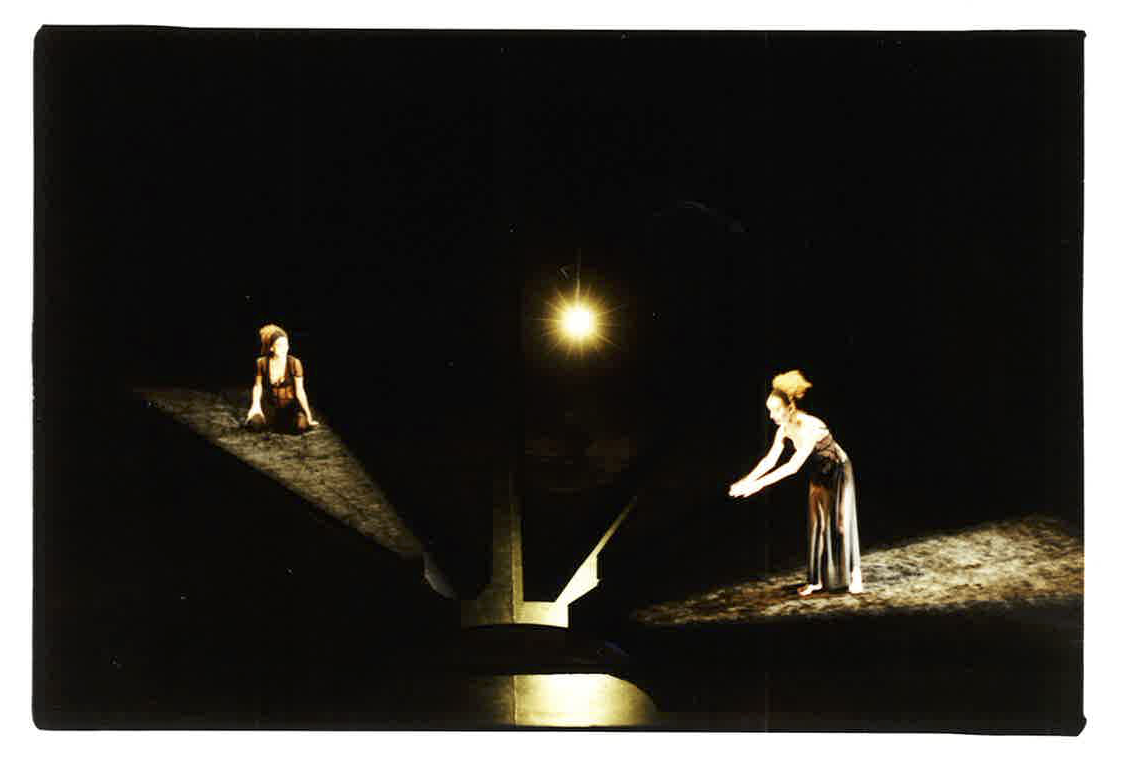

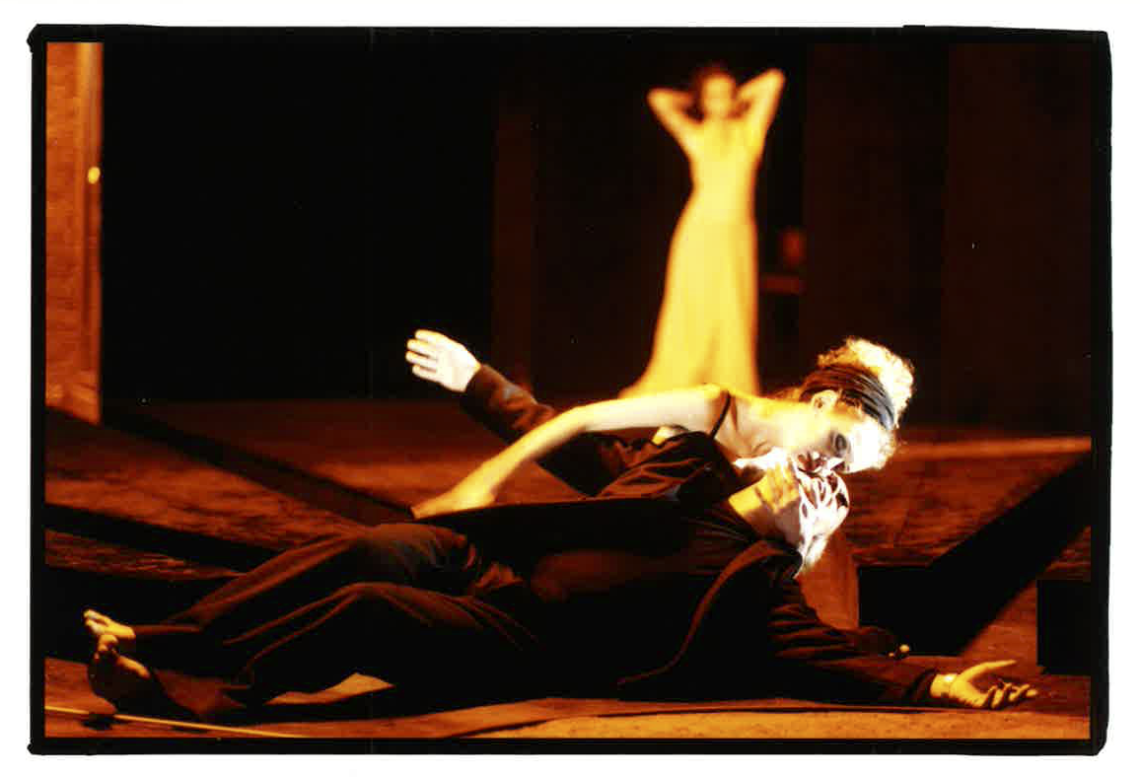

Top right: Janni Goslinga and Sara De Bosschere in 'Mind the Gap'. Photo by Chris van der Burght. APGRD ID: 6231. Bottom right: Sara De Bosschere and Wim van der Grijn in 'Mind the Gap'. Photo by Chris van der Burght. APGRD ID: 6230.

Mind the Gap, Hertmans’ second play for the Kaaitheater, tells the stories of three women who are unwilling to play the restricted roles set out for them in their ancient myths. All three, the programme note reminds us, speak loudly and clearly in his monologues, saying a radical “NO” (NEE) to the patriarchal worlds in which they find themselves. Antigone says NEE to Creon’s law that she ought to leave her dead brother unburied; Medea, having lost everything to be with Jason, says NEE to his announcement that he will marry another woman for political gain; and Clytemnestra says a loud NEE to the possibility that she might forgive her husband for sacrificing their daughter Iphigenia in support of his military expedition to Troy. The radical NEE that is the defining feature of these female characters, however, is not simply radical because it is the Flemish nee rather than the Greek οὐ. It is also the Flemish nee rather than the French non. In keeping a diary of his engagement with Antigone, Hertmans is echoing the practice of the Belgian novelist Henry Bauchau, who kept a diary while writing his own version of the story of Antigone in a French-language novel published in 1997 (part of a trilogy he had begun in 1990 with a novel about Oedipus). Bauchau narrates the novel from the point of view of Antigone herself – “appropriating”, as Hertmans has it, the young woman’s own voice.

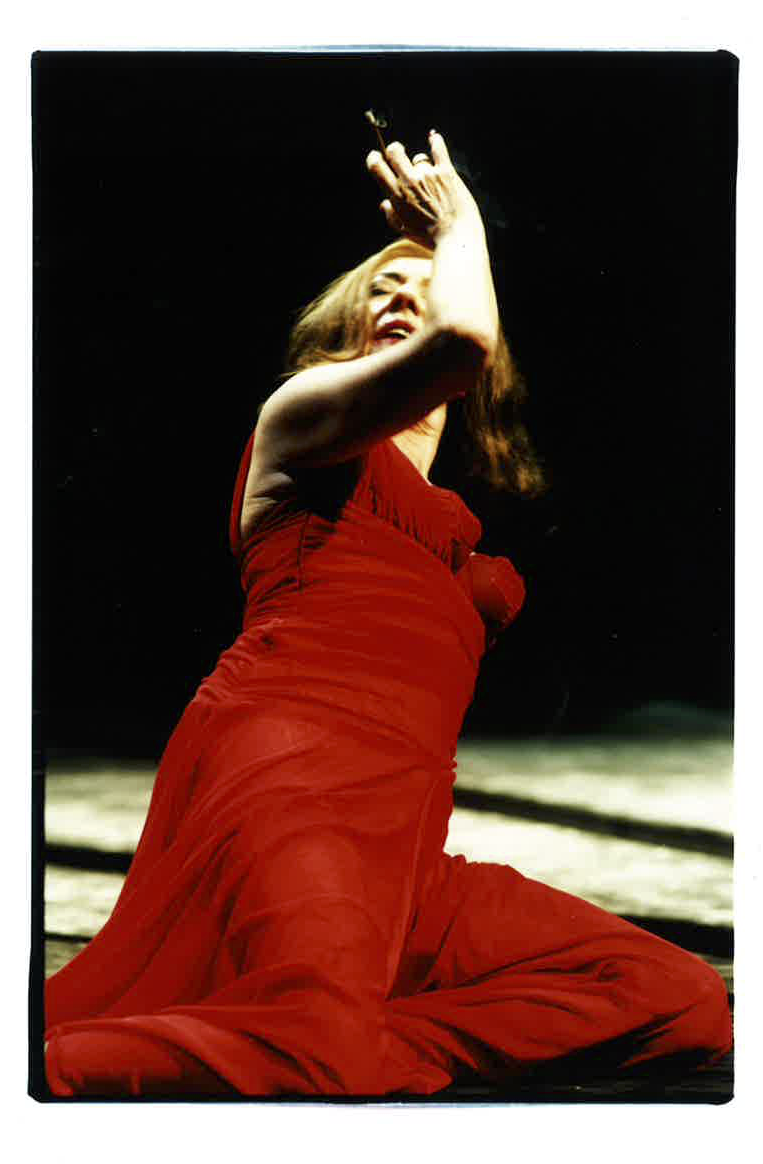

Mind the Gap, Hertmans’ second play for the Kaaitheater, tells the stories of three women who are unwilling to play the restricted roles set out for them in their ancient myths. All three, the programme note reminds us, speak loudly and clearly in his monologues, saying a radical “NO” (NEE) to the patriarchal worlds in which they find themselves. Antigone says NEE to Creon’s law that she ought to leave her dead brother unburied; Medea, having lost everything to be with Jason, says NEE to his announcement that he will marry another woman for political gain; and Clytemnestra says a loud NEE to the possibility that she might forgive her husband for sacrificing their daughter Iphigenia in support of his military expedition to Troy. The radical NEE that is the defining feature of these female characters, however, is not simply radical because it is the Flemish nee rather than the Greek οὐ. It is also the Flemish nee rather than the French non. In keeping a diary of his engagement with Antigone, Hertmans is echoing the practice of the Belgian novelist Henry Bauchau, who kept a diary while writing his own version of the story of Antigone in a French-language novel published in 1997 (part of a trilogy he had begun in 1990 with a novel about Oedipus). Bauchau narrates the novel from the point of view of Antigone herself – “appropriating”, as Hertmans has it, the young woman’s own voice. Celia Nufaar in 'Mind the Gap'. Photo by Chris van der Burght. APGRD ID: 6232. Alongside Hölderlin, Kierkegaard, Müller, Shelley, Lacan, Freud and a number of other infamous readers of Sophocles’ play, Hertmans quotes from Bauchau’s diary in his own production diary, translating into Flemish the text Bauchau wrote in French from Paris, having left his native Belgium in 1946. It is not, however,in order to benefit from Bauchau’s analysis of Antigonethat Hertmans quotes passages from his diary (though Bauchau was himself a psychoanalyst and friend to the likes of Lacan and Derrida as well as a novelist and poet). Instead, Hertmans focuses on making readers aware of the differences between his and his compatriot’s versions of the play. Unlike Bauchau, Hertmans does not want to be Antigone. He refutes in his own diary Bauchau’s claim in a letter to Alain Badiou that “writing about Antigone is writing about the desire to become a woman”. Hertmans responds instead that a male author must resist appropriating Antigone’s female voice: “writing about Antigone […] is resisting her terrible attraction, resisting the temptation, as a man, to identify with her integrity and in this way to fatally corrupt her […]. You are on the opposite side”. As well explicitly pointing out the ‘gaps’ to which Mind the Gap responds and lamenting the over-theorisation of Sophocles’ heroine in general, Hertmans’ diary confronts appropriations, like Bauchau's, of Antigone’s voice in particular: “My god. Author, shut up and let her speak through your mouth”. This attention to how Antigone speaks rather than how she ought to be interpreted is particularly fitting for the author of a Flemish version of a Greek tragedy. At the same time as he rails at male authors, who in their desire to take on her dissenting position appropriate Antigone’s femininity, Hermans also implicitly accuses Bauchau of having sublimated Antigone’s language to his own novelistic French. As the final words of his diary, Hertmans leaves readers not only with Shelley’s famous pronouncement that “Some of us have in a prior existence been in love with Antigone”, but also with the Dutch novelist Cees Nooteboom’s comment that “Antigone can never be innocent again now that she has read herself”. This is followed immediately by Lacan’s dictum that Antigone is “no other than the break that the very presence of language inaugurates in man”.

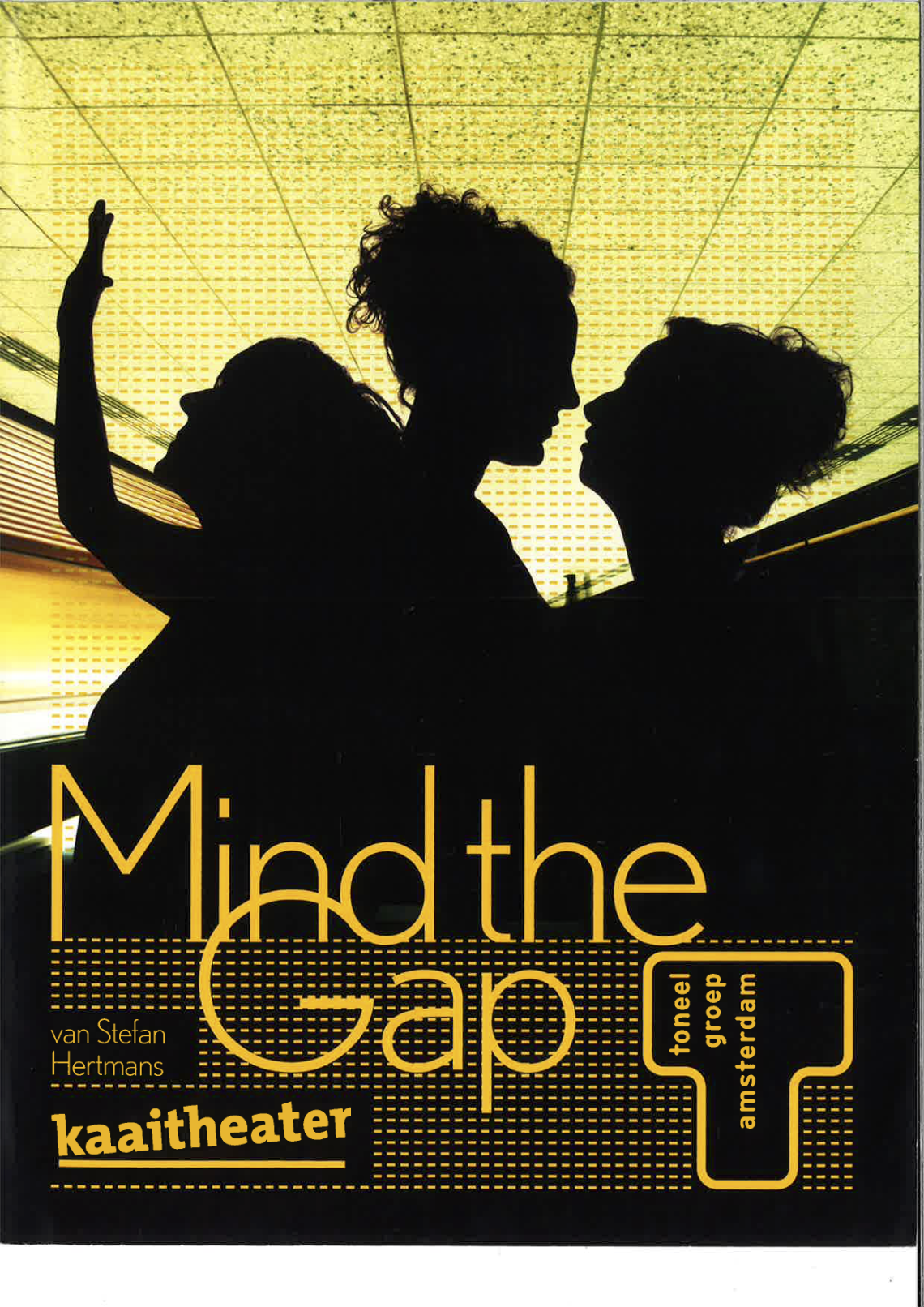

Celia Nufaar in 'Mind the Gap'. Photo by Chris van der Burght. APGRD ID: 6232. Alongside Hölderlin, Kierkegaard, Müller, Shelley, Lacan, Freud and a number of other infamous readers of Sophocles’ play, Hertmans quotes from Bauchau’s diary in his own production diary, translating into Flemish the text Bauchau wrote in French from Paris, having left his native Belgium in 1946. It is not, however,in order to benefit from Bauchau’s analysis of Antigonethat Hertmans quotes passages from his diary (though Bauchau was himself a psychoanalyst and friend to the likes of Lacan and Derrida as well as a novelist and poet). Instead, Hertmans focuses on making readers aware of the differences between his and his compatriot’s versions of the play. Unlike Bauchau, Hertmans does not want to be Antigone. He refutes in his own diary Bauchau’s claim in a letter to Alain Badiou that “writing about Antigone is writing about the desire to become a woman”. Hertmans responds instead that a male author must resist appropriating Antigone’s female voice: “writing about Antigone […] is resisting her terrible attraction, resisting the temptation, as a man, to identify with her integrity and in this way to fatally corrupt her […]. You are on the opposite side”. As well explicitly pointing out the ‘gaps’ to which Mind the Gap responds and lamenting the over-theorisation of Sophocles’ heroine in general, Hertmans’ diary confronts appropriations, like Bauchau's, of Antigone’s voice in particular: “My god. Author, shut up and let her speak through your mouth”. This attention to how Antigone speaks rather than how she ought to be interpreted is particularly fitting for the author of a Flemish version of a Greek tragedy. At the same time as he rails at male authors, who in their desire to take on her dissenting position appropriate Antigone’s femininity, Hermans also implicitly accuses Bauchau of having sublimated Antigone’s language to his own novelistic French. As the final words of his diary, Hertmans leaves readers not only with Shelley’s famous pronouncement that “Some of us have in a prior existence been in love with Antigone”, but also with the Dutch novelist Cees Nooteboom’s comment that “Antigone can never be innocent again now that she has read herself”. This is followed immediately by Lacan’s dictum that Antigone is “no other than the break that the very presence of language inaugurates in man”.  Below: Programme for 'Mind the Gap', APGRD ID: 6288.

Below: Programme for 'Mind the Gap', APGRD ID: 6288.

That linguistic confrontation, and the superiority of a Flemish-language version in conveying the heterodoxy of Antigone’s own voice, should close Antigone Aantekeningen is not only the result of a production that privileges the voices of women who confront the language of authority in their plays. It also exemplifies the kinds of confrontations and conversations between French- and Flemish-language adaptations of Greek tragedy that have characterised the rewriting of ancient plays by Belgian writers since the earliest Flemish adaptations. Shortly before Mind the Gap gave voice to the figure of Clytemnestra, Brussels had been the scene of a French-language adaptation of the Oresteia, Le Sang des Atrides by the Théâtre en Liberté at the Théâtre des Martyrs, only a few minutes walk down the Boulevard Baudoin from the Kaaitheater (a walk that would take in both of Belgium’s national theatres, the Théâtre National Wallonie and the Koninklijke Vlaamse Schouwburg). Indeed, the Flemish-language Oresteia of 1946 was translated by Herman Teirlinck, a prominent member of the Vlaamse Volkstoneel who found in Aeschylus’ trilogy an analogue for the cultural emancipation of the Flemish language that had returned to prominence during Second World War (and would continue until the designation of the frontière linguistique in 1962). Although occasionally prone to all the eccentricity of Belgian surrealism (“Cynical and meaningful: the wife of Creon is called Eurydice”, Hertmans writes cryptically, with no further explanation), Hertmans’ diary is testimony to a linguistic struggle that marks the reception of Greek tragedy in Belgium. With his attention to the appropriation of Antigone’s oppressed and dissenting voice by French-language authors, critics and philosophers, Hertmans sets his own production up as a response to the over-intellectualising of Greek drama on the Bruxellois stage. With her loud Flemish NEE, he suggests, Antigone might finally be speaking in her own voice rather than in the voice of an author who has appropriated her. In his production, it is not only the three heroines from Greek myth who refuse to dwell silently in the ancient underworld, but also the Flemish-language adaptations of Greek tragedy that refuse to be consigned to the underground realms of Belgian theatre history.

Find out more

- About Marchella Ward

- To read further about the complexities of translating ancient plays, see Cécile Dudouyt's Short Guide on Translation.

- To hear more about the process of translating a very different Antigone, you can listen to Frank McGuinness discuss his methods of translating ancient plays from an in-conversation event with Fiona Macintosh (APGRD Director) from 2009.