A guest post by Máirín O'Hagan

In 2015, when Fiona Macintosh, Claire Kenward and Tom Wrobel were working on the APGRD’s first multimedia interactive eBook, Medea, a performance history, they commissioned two scenes from Euripides’ Medea as short films, performed in the original Greek. Since then, the company that produced these films, Barefaced Greek, under the direction of APGRD Artist Associate and Advisory Board Member, Helen Eastman, have gone on to produce a number of other short films in Greek, with English subtitles, based on ancient dramatic texts. Ahead of their event at the ICS, where they showed and discussed the films, we asked Máirín O’Hagan, Barefaced Greek’s producer (top left), to tell us more about their creative process.

In 2015, when Fiona Macintosh, Claire Kenward and Tom Wrobel were working on the APGRD’s first multimedia interactive eBook, Medea, a performance history, they commissioned two scenes from Euripides’ Medea as short films, performed in the original Greek. Since then, the company that produced these films, Barefaced Greek, under the direction of APGRD Artist Associate and Advisory Board Member, Helen Eastman, have gone on to produce a number of other short films in Greek, with English subtitles, based on ancient dramatic texts. Ahead of their event at the ICS, where they showed and discussed the films, we asked Máirín O’Hagan, Barefaced Greek’s producer (top left), to tell us more about their creative process.

When approaching an ancient, foreign text, an adaptor has to make choices. Do you want to make your version as close to what an ancient Greek audience might have seen, or to translate what their experience might have felt like? Do you highlight the strangeness of cultural and temporal distance, or connect the text to a contemporary audience through modern parallels— x is to a 5th Century Athenian as y is to a globe-trotting millennial—? When we (Helen Eastman directing, and me producing) set up Barefaced Greek in 2015, our first priority was to produce ancient texts in their original ancient languages. Since we were starting with the strange and alienating as far as language was concerned, we wanted to temper that by choosing accessible media and contexts that would help draw in our audience, hopefully encouraging a shared love of the wonderful Greek language.

Right: Still from The Watchman. Image reproduced here by kind permission of Barefaced Greek.

Right: Still from The Watchman. Image reproduced here by kind permission of Barefaced Greek.

Having decided to retain the original language of Greek drama, we chose to compromise on other types of ‘authenticity’. As cinema rather than theatre, the films are, by necessity, modern. The title of the company, ‘Barefaced Greek’ acknowledges that what was once performed on huge, open-air stages, with amplifying, fixed-expression, dramatic masks, will not produce the same effects on camera. The naturalistic images and up-close intimacy of the camera challenge the sense of public, shared experience that comes from being an Athenian citizen sitting amongst many others in a festival in Athens, for Athens, and about Athenian concerns. Moreover, original Greek drama used the chorus, a body of performers chosen from the community, whose position between watching and advising bridges the gap between the audience and actors. The connection created by a chorus is hard to replicate so, with a view to adapting that experience, director Helen Eastman chose to explore the moments when actors break from cinematic convention to look directly into the camera lens. The direct address is theatrical, but it also connects the actor directly to their audience. This is when they speak to you.

In choosing our settings for films, we try to keep a level of generality to avoid overly locating the text in one place or time, hoping to leave flexibility for the audience to take the texts into their own imaginations. When staging a new translation of a play for a theatre, there is an opportunity to set a Greek tragedy within a specific war or political context, and to overlay it with our impressions of another part of history, connecting the audience via parallels. We have endeavoured to leave some ambiguity so that these films can showcase language over interpretation, though there are inevitable exceptions to this.

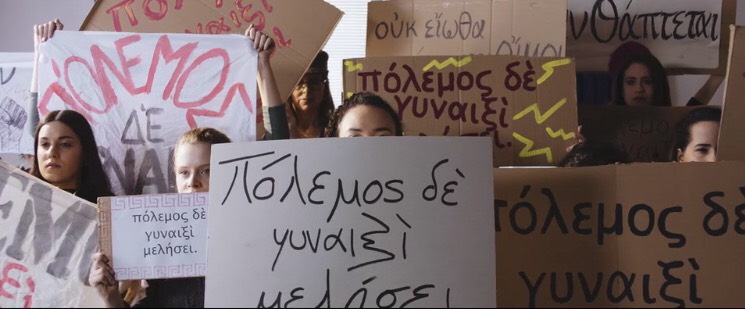

Still from Lysistrata. Image reproduced here by kind permission of Barefaced Greek.

Still from Lysistrata. Image reproduced here by kind permission of Barefaced Greek.

The most obvious exception is our Lysistrata, which we made quickly, in response to the shocking revelations of the US elections, and the subsequent Women’s protests in 2017. Images of elderly women holding banners which read ‘I can’t believe I still have to protest this shit’, made the women’s protests of the 1960s seem a very long time ago, but also reminded us of the 2500 year old protests of Aristophanes’ Lysistrata or Assembly Women. When the ‘pussy hat’ made it’s way into the protests of early 2017, Lysistrata became an obvious choice for our next film shoot. The weaving speech, in which Lysistrata compares how she would approach government to the way she would turn dirty fleece into warm clothing, can be hard to make resonate in the modern, western world, where women rarely count the production of clothing fresh from the sheep among their daily duties, and where audiences might not recognise words such as ‘carding’ or ‘distaff’ in English, let alone Greek. The decision to make knitting part of the Women’s protest, however, ties into a long history, both of women working with textiles and of using textiles as a form of protest, be it knitting at the guillotine, the ‘peace scarf’ anti-trident protest, or Casey Jenkins famous vaginal art installation. When the leader of the free world’s chauvinist boasts prompted thousands to take up their knitting needles, it seemed the obvious time for Lysistrata the woolworker-protester to raise her head, to mix sex-strikes with statement knitwear, and assume her context amid current events.

The chorus again became important to us when we were thinking about Lysistrata. Our first films focus on monologues and duologues spoken by protagonists. However, collectivity is key to protest. Eastman’s decision to use mirrors as Lysistrata rehearses her speech highlights the relationship between oppression and isolation on the one hand, and the joyful solidarity of protest on the other. As her speech continues, Lysistrata begins to see the crowds of women who will join her, who share her need to protest, building in numbers in her mirror reflection.

Still from Lysistrata. Image reproduced here by kind permission of Barefaced Greek.

Still from Lysistrata. Image reproduced here by kind permission of Barefaced Greek.

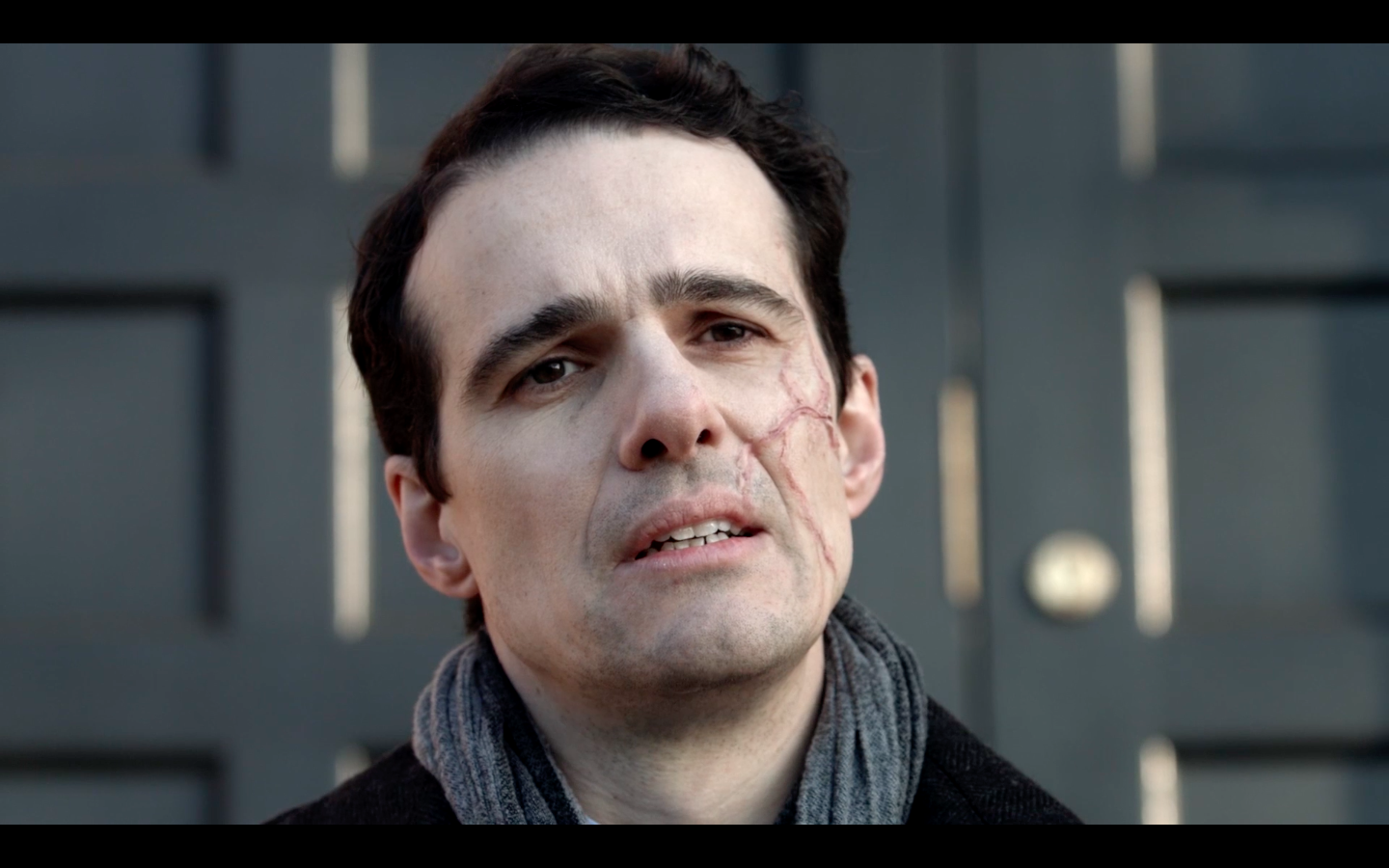

Our film Agamemnon: The Homecoming depicts King Agamemnon (Jake Harders) returning from ten years of war in Troy and addressing the people of Argos on the doorstep of his palace, before he enters his home. He has not seen his wife for ten years, around the time he sacrificed their young daughter Iphigenia for the sake of the war. His lingering on the doorstep is significant, as when he does cross the threshold, the repercussions of his actions immediately catch up with him. Eastman chose to keep this positioning on the doorstep fixed, staying true to the specifications of the original play, but rather than speaking to the assembled crowds of an Athenian theatre audience, Agamemnon’s speech is delivered to the television cameras of the press, where every nuance of his delivery will be picked up by the public, even as he crosses beyond the threshold to meet his fate (writing this is making me think of the unforgettable moment when David Cameron entered 10 Downing Street upon resigning from government to sing that song. There is no rest for the political man, even when he closes the palace door…).

The problem for modern directors is that Agamemnon’s ominous position on that threshold holds little significance to those who don’t know his context— that he has been long at war, that he has seen Troy burning, that he has enslaved its captive population, that he has killed his own daughter. Eastman uses flashbacks to enlighten or remind the audience that whilst Agamemnon presents himself as every bit the charming politician, the darker truths of his life lurk close to the surface of his public persona, with director of photography Thomas Bradley’s intercutting of exposing and obscuring camera angles around his face - his mask - reflecting this duplicity.

Still from Agamemnon's Homecoming. Image reproduced here by kind permission of Barefaced Greek.

Still from Agamemnon's Homecoming. Image reproduced here by kind permission of Barefaced Greek.

In other instances, we have used setting to inspire our adaptations. We have an upcoming series of films made in Greece going into post-production this year, where our exploration of the role of the chorus will be further developed. We were also incredibly lucky to be invited to make a film in the Victoria & Albert Museum, prior to our exhibition there in March last year. Surrounded by the stone bodies of classical figures and gods, we thought that this setting would provide a wonderful opportunity to play with the relationship between the divine and the human. We chose the fiery interaction between the defeated Poseidon and the vengeful goddess Athena from Trojan Women, to set amid the artworks, where the twisting stone structures around them represented the mortality of human lives. The gods themselves (Rebecca Scott and Joey Akubeze) embody living flesh, and the humans around them are reduced to a museum of mortal playthings.

Despite our wish to privilege the ancient text, we have, of course, had to include translations. Here an act of adaptation cannot be avoided. Our approach with translations for subtitles has been to keep them simple enough to be read alongside the film. Whilst I love to create translations that reflect the word order of the Greek as much as possible, so that audiences can pair the Greek and translation, brevity has to be key. A final act of practical adaptation we have tried to consider is that of presentation to the public. Ancient Greek plays were, in many ways, a democratic form of entertainment, performed for huge numbers of the population in festivals designed to make people feel part of their community. As modern audience memberswe will always be watching Greek theatre as outsiders, watching drama in a foreign language, from an ancient time. The number of people who learn classical Greek is relatively small, and very few could listen to a film in Greek with aural fluency, but the number of people who use YouTube is enormous. We wanted to translate the accessibility of Greek drama in Athens of the fifth century BCE to an online community where people share content through social networks, find it commonplace rather than elitist, and where there are as few barriers to access as possible. Our first four films are out there now, for anyone who’d like an accessible route into this strange and ancient community.

Find out more

You can watch the Barefaced Greek films on YouTube:

- Lysistrata

- The Watchman (Agamemnon)

- Agamemnon: The Homecoming

- Trojan Women: Poseidon and Athena

- Or read more about the project on their website.

- To see the earliest Barefaced Greek films of Medea, and to explore the performance history of Euripides' Medea - through digitised archival material, video clips, and bespoke interviews with academics and creatives - see the APGRD's free interactive/multimedia ebook